The evolution of aviation is one of the most remarkable achievements of the modern era. In just over a century, we’ve progressed from fragile wood-and-fabric contraptions barely staying aloft to sophisticated jetliners cruising effortlessly across the globe. Alongside this extraordinary journey, aviation has matured into one of the most regulated and safety-conscious industries in the world. Much of that structure is owed to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the standards it upholds for pilot training and certification. To understand the current landscape of aviation, it’s important to look at where it began.

Early Concepts and the Dawn of Flight

Long before humans took to the skies in powered machines, the dream of flight was alive in the minds of artists, inventors, and scientists. Leonardo da Vinci, in the 15th century, was one of the first to study the mechanics of flight with scientific precision. Though he never built a flying machine that flew, his notebooks were filled with detailed sketches of ornithopters—devices that mimicked the flapping wings of birds—and parachutes. His designs demonstrated an early understanding of lift, drag, and flight controls, laying theoretical groundwork that wouldn’t be fully appreciated until centuries later.

The first actual human flights occurred not with airplanes but with balloons. In 1783, the Montgolfier brothers of France launched the first successful manned hot air balloon, carrying passengers into the sky in a tethered ascent. That same year, Jacques Charles and Nicolas-Louis Robert flew the first hydrogen balloon, introducing a new form of lighter-than-air flight. These achievements proved that controlled ascent and descent were possible, and for the next century, balloons—and later airships (dirigibles)—were the dominant form of aviation. Though they lacked precise control, they provided the first glimpses of aerial navigation and sparked widespread fascination with flight.

The Rise of Powered Aviation

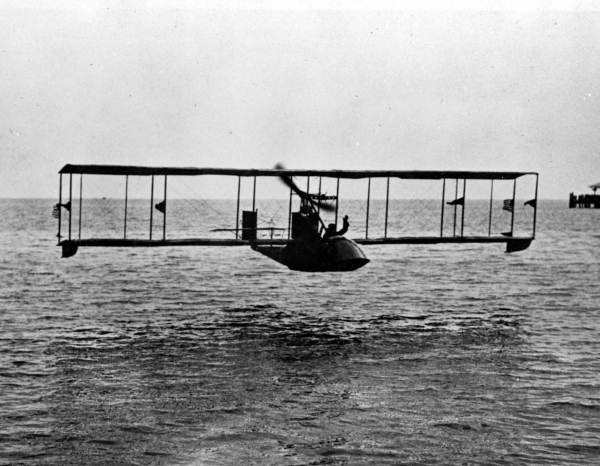

The history of powered aviation begins decisively on December 17, 1903, when the Wright brothers made the first controlled, sustained flight of a powered, heavier-than-air aircraft. That flight lasted just 12 seconds and covered 120 feet, but it was a pivotal moment in human history. In the years that followed, aviation progressed rapidly. Innovators and aviators around the world built increasingly capable aircraft, competing for speed, altitude, and endurance records. In the 1920s and 1930s—the “Golden Age of Aviation”—commercial airlines began forming, air mail routes expanded, and aviation became more reliable and glamorous. Pilots like Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart became global icons.

World War II brought explosive growth in aviation technology. The need for high-performance fighters, bombers, and transport aircraft pushed manufacturers to develop faster, more powerful, and more durable machines. In the postwar years, this knowledge transferred to civilian aviation. Airports expanded, airline networks connected continents, and aviation became a mainstream mode of transportation. The introduction of jet engines in commercial aviation during the 1950s further revolutionized air travel, drastically reducing travel times and increasing capacity.

The world’s first airline to operate a scheduled, fixed-wing passenger flight was the St. Petersburg–Tampa Airboat Line, which began service on January 1, 1914. Founded by Percival Fansler and piloted by aviation pioneer Tony Jannus, the airline used a Benoist XIV flying boat to carry one paying passenger at a time across Tampa Bay, Florida. The first passenger was Abram C. Pheil, the former mayor of St. Petersburg, who paid $400 at auction for the historic seat—equivalent to over $11,000 today. Though the route was only about 21 miles and the airline operated for just a few months, making fewer than 100 flights, it proved that commercial air travel was possible and could save significant time compared to land or sea routes. This short-lived but groundbreaking service marked the birth of the airline industry and set the stage for a century of global air transportation.

The Rise of Regulation (FAA)

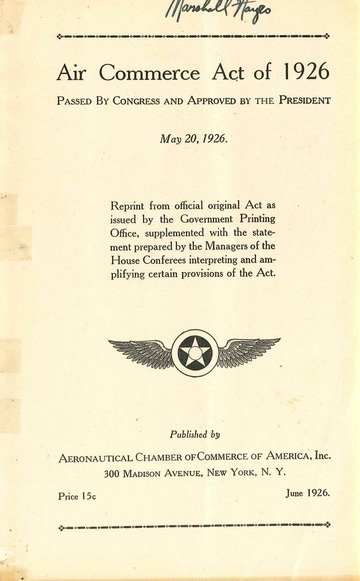

With aviation’s rapid expansion in the early 20th century came growing risks—and a clear need for federal oversight. In the 1920s, commercial aviation was in its infancy, and while aircraft technology was improving, the infrastructure and regulatory framework lagged behind. Flights operated with minimal communication, navigational aids were sparse, and safety procedures were inconsistent. Accidents were frequent, and public trust in air travel remained fragile. To address these issues, the U.S. government passed the Air Commerce Act of 1926, the first major piece of federal aviation legislation. Signed into law by President Calvin Coolidge, the Act authorized the Department of Commerce to regulate civil aviation. It established responsibilities such as pilot licensing, aircraft certification, route marking, and accident investigation—marking the birth of federal aviation regulation in the U.S.

As aviation continued to grow—particularly with the rise of passenger airlines in the 1930s—the government recognized the need for a more comprehensive and independent body to oversee safety, operations, and economic regulation. This led to the passage of the Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Act created the Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA), which was empowered to regulate airline fares, routes, and safety standards. It also established the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), a semi-independent agency responsible for investigating accidents and making decisions on airline economic regulation, such as granting new routes and approving mergers.

In 1940, President Roosevelt reorganized the CAA, splitting it into two entities: the CAA, which remained under the Department of Commerce to handle safety regulation and air traffic control, and the CAB, which became an independent agency tasked with economic regulation and accident investigations. This structure served the aviation industry throughout World War II and into the early years of the Jet Age. However, as aircraft became faster and more numerous, the limitations of the system became apparent—particularly in the management of high-altitude and en route air traffic.

In the early days of commercial aviation, air traffic control (ATC) was not a government-run system, but instead was initially operated by the airlines themselves. As passenger flights became more common in the 1920s and 1930s, the need to coordinate air traffic—especially around busy airports—became increasingly apparent. To address this, a group of airlines began organizing their own communication and coordination services to prevent midair collisions and improve efficiency. The first formal air traffic control tower in the U.S. was established in 1930 at Cleveland Municipal Airport, and it was staffed not by government employees, but by personnel hired by the airlines. These early controllers used visual signals, flags, and basic radio communication to guide aircraft. It wasn’t until the Air Commerce Act of 1926 and, more significantly, the expansion of the federal role in the late 1930s that the U.S. government began assuming responsibility for regulating and operating air traffic control. However, the system remained limited in scope for high-altitude and en route traffic. That changed dramatically after the 1956 Grand Canyon midair collision, in which two commercial airliners crashed in uncontrolled airspace, killing all 128 people aboard. The disaster shocked the nation and made it painfully clear that the existing system, divided between civil and military control with fragmented communication, could no longer ensure safety in increasingly crowded skies. Public outcry and media coverage put pressure on lawmakers to act swiftly.

In response, Congress passed the Federal Aviation Act of 1958, which created the Federal Aviation Agency—later renamed the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) when it was integrated into the newly formed Department of Transportation in 1967. The FAA was given sweeping authority over all aspects of civil aviation, including air traffic control, aircraft certification, airport standards, and pilot certification. It also assumed responsibility for developing the National Airspace System (NAS), a coordinated network for managing the movement of all aircraft, civilian and military, across the United States.

In 1967, the same year the FAA was moved under the newly created Department of Transportation, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) was also established to take over the role of accident investigation from the CAB.This shift allowed the CAB to focus solely on its economic regulatory functions, such as overseeing airline fares, routes, and market entry. The CAB continued to function independently, focusing on economic regulation and accident investigation, until it was dissolved in 1985 as part of deregulation efforts.The NTSB was tasked with determining the probable causes of transportation accidents and issuing safety recommendations to prevent future incidents. It operates independently from regulatory agencies like the FAA to ensure unbiased investigations and covers all major modes of transportation, including aviation, highways, marine, rail, and pipelines.

The establishment of the FAA marked a turning point in aviation history. For the first time, a single federal agency held unified authority to manage airspace, enforce safety standards, and oversee both technological and operational aspects of the aviation industry. This centralized approach, forged in the wake of tragedy, laid the groundwork for the modern system of aviation safety and air traffic management that exists today.

Modern FAA

Today, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) serves as the primary federal agency responsible for regulating and overseeing all aspects of civil aviation in the United States. The FAA’s primary mission is to provide the safest, most efficient aerospace system in the world. To effectively manage these duties across the vast U.S. airspace, the FAA is organized into several regional offices, including 78 Flight Standards District Offices (FSDOs) located throughout the country. FSDOs serve as the FAA’s local field offices, providing critical oversight and support for pilots, mechanics, and operators by conducting inspections, issuing certificates, investigating incidents, and offering educational outreach. This decentralized structure allows the FAA to maintain a strong presence at the grassroots level, ensuring that safety and regulatory compliance are upheld consistently nationwide.

Within these Flight Standards District Offices, one of the most important roles is filled by Aviation Safety Inspectors (ASIs). These trained FAA officials are responsible for enforcing safety regulations by conducting inspections, certifying pilots and mechanics, and investigating incidents. ASIs serve as the FAA’s eyes and ears on the ground, ensuring that aviation operators comply with federal standards and helping to maintain the overall safety of the National Airspace System.

The FAA WINGS program is a voluntary pilot proficiency initiative designed to encourage ongoing education and training for pilots to enhance aviation safety. Pilots earn credits by completing various activities such as online courses, flight training, and safety seminars, which help maintain and improve their flying skills and knowledge. Complementing this program is the FAA Safety Team (FAASTeam), a collaborative effort between the FAA and the aviation community that promotes safety through education, outreach, and risk management resources. The FAASTeam organizes safety workshops, seminars, and online courses aimed at preventing accidents by raising awareness of common risks and encouraging best practices. Together, the WINGS program and FAASTeam foster a culture of continuous learning and proactive safety among pilots and aviation professionals.

Pilot and Aircraft Certification

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) issues several levels of pilot certificates, each representing increasing degrees of training, experience, and privileges. These certificates allow pilots to operate progressively more complex aircraft and conduct more advanced types of flying:

- Student Pilot Certificate: The very first certificate a new pilot obtains. It allows solo flight under the supervision of a flight instructor, typically during training. Student pilots cannot carry passengers or fly for compensation and must adhere to specific limitations.

- Sport Pilot Certificate: Designed for flying light-sport aircraft (LSA), this certificate requires fewer training hours than a private pilot certificate. It restricts pilots to daylight, good weather conditions, and smaller, simpler aircraft. Sport pilots can carry one passenger but have operational limitations on aircraft weight and speed.

Private Pilot Certificate: The most common initial full pilot certificate. It allows holders to fly a broad range of aircraft for personal and recreational purposes. Private pilots can carry passengers but cannot be compensated for flying. The certificate requires more stringent training, experience, and knowledge than the sport pilot certificate. - Commercial Pilot Certificate: Permits pilots to be compensated for their flying services. Commercial pilots demonstrate advanced skills and knowledge and often operate charter flights, banner towing, or other commercial activities. They are not authorized to serve as airline pilots without further certification.

- Airline Transport Pilot (ATP) Certificate: The highest level of pilot certification, required to serve as captain or first officer for scheduled airlines. It requires significant flight experience (typically at least 1,500 hours), advanced knowledge, and passing rigorous practical and written exams. ATP holders have full privileges to operate virtually any aircraft type.

- Flight Instructor Certificate: Allows pilots to train student pilots and endorse them for solo flights and certifications. Instructors must hold a commercial pilot certificate and meet additional qualifications.

Each certificate builds upon the previous one, with increasing responsibilities, privileges, and requirements. Additionally, pilots earn ratings and endorsements that specify the types of aircraft they can fly (such as instrument, multi-engine, seaplane) or special aircraft characteristics (such as tailwheel or high-performance aircraft). Aviation certification for both airmen (pilots) and aircraft is structured around the concepts of category and class to clearly define the scope and limitations of qualifications and capabilities. This ensures pilots are trained and tested for the specific types of aircraft they operate and that aircraft meet regulatory standards appropriate to their use.

Airman Certification Categories

Categories refer to broad groups of aircraft based on operating characteristics and design. Primary categories include:

- Airplane: Fixed-wing aircraft with engines.

- Rotorcraft: Helicopters and gyroplanes.

- Glider: Engine-less heavier-than-air aircraft.

- Lighter-than-air: Balloons and airships.

- Powered-lift: Aircraft capable of vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) that transition to forward flight.

Airman Certification Classes

Within each category, class further refines the type of aircraft. For example, within the airplane category, classes include:

- Single-engine land

- Multi-engine land

- Single-engine sea

- Multi-engine sea

A pilot’s certificate specifies both the category and class for which they are rated. For example, a private pilot certificate with an airplane single-engine land rating ensures the pilot is authorized to operate those specific aircraft. To add a new class or category, pilots must complete additional training and pass relevant practical tests.

Aircraft Certification Categories

Aircraft certification categories describe the intended use and operational limitations of the aircraft. Common categories include:

- Normal category: Aircraft intended for non-acrobatic operations and limited maneuvers, typically carrying passengers or cargo.

- Utility category: Aircraft certified for limited acrobatic maneuvers such as spins or steep turns, with higher structural requirements.

- Acrobatic category: Aircraft designed for full aerobatic maneuvers.

- Transport category: Larger aircraft intended for commercial passenger or cargo transport with stringent safety standards.

- Manned free balloons: Balloons designed to carry passengers.

Aircraft Certification Classes

Within each category, the class further specifies characteristics like the number of engines or landing gear type. Common airplane classes are:

- Airplane: Fixed-wing aircraft with engines.

- Rotorcraft: Helicopters and gyroplanes.

- Glider: Engine-less heavier-than-air aircraft.

- Lighter-than-air: Balloons and airships.

- Powered-lift: Aircraft capable of vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) that transition to forward flight.

This classification ensures aircraft meet appropriate regulatory standards based on their design and use.

Type Rating

A type rating is a special certification a pilot must obtain to operate certain large or complex aircraft. Unlike general pilot certificates and class ratings, which cover broad groups of aircraft, type ratings are specific to a particular make and model.

The FAA requires a type rating for:

- Aircraft with a maximum gross takeoff weight over 12,500 pounds.

- Turbojet-powered airplanes of any size.

- Certain other complex aircraft as determined by the FAA.

Examples of aircraft requiring type ratings include the Boeing 737, Airbus A320, and Citation business jets. To earn a type rating, a pilot must complete specialized training focused on that aircraft’s systems, performance, and operating procedures, followed by a practical test with an FAA examiner or authorized check airman.

Type ratings ensure pilots have the specialized knowledge and skills to safely operate advanced or large aircraft and are legally required to act as pilot-in-command of these aircraft.

Here are some example to help illustrate this better:

- A pilot holding a private pilot certificate with an airplane single-engine land rating can fly small piston-powered airplanes like a Cessna 172 for personal use but not seaplanes or multi-engine aircraft.

- A commercial pilot with a multi-engine land class rating can operate aircraft such as the Beechcraft Baron, which has two engines and operates from land.

- An airline transport pilot (ATP) flying a Boeing 737 must have a specific type rating for that aircraft, in addition to their ATP multi-engine land certificate.

A seaplane pilot requires a single-engine sea class rating to operate floatplanes or amphibious airplanes like the de Havilland Beaver.

The evolution of aviation reflects a remarkable journey from early dreams of human flight to a highly sophisticated and regulated global industry. Beginning with pioneering inventors like Leonardo da Vinci and balloonists of the 18th century, powered flight was achieved in the early 20th century and quickly transformed transportation, commerce, and warfare. Alongside technological advancements, the development of federal oversight—culminating in the creation of the Federal Aviation Administration—has been crucial to ensuring safety, efficiency, and reliability in the skies. Today’s aviation system relies on rigorous pilot training, comprehensive regulations, and collaborative safety programs to uphold the highest standards, enabling millions of people to travel safely every day and connecting the world like never before.